Introduction

Videogames are filled with conversations. These range from simple barks to deep and varied dialogue trees, but they’re fairly prevalent regardless of implementation.

And it makes sense, too. People like stories, and stories are typically built on characters.

Despite this fairly natural desire for dialogue, games used to be pretty devoid of conversations. This struck me as particularly odd in RPGs where groups of people frequently set out on quests to save the world. After all, one would assume the journey would foster some banter and camaraderie.

Cutscenes eventually filled the void, but it took a while for another mechanism to catch on: letting the player manually choose to speak to their followers.

Planescape: Torment was one of the first titles to do this, and its discussions on the Circle of Zerthimon remain one of my favourite examples of player-initiated dialogue.

“No wonder my back hurts; there’s a damn novel written there.”

Planescape: Torment opens up with its scarred protagonist, The Nameless One (TNO), waking up in a morgue. A talking skull quickly floats by initiating a conversation.

We soon find out that Planescape: Torment is not afraid of being verbose. Dialogue is plentiful and it’s buffeted by descriptions, creating entire paragraphs that read like a novel. The Planescape cant — 19th Century British slang — adds further colour to the text.

Morte, the talking skull, informs us that TNO is effectively immortal as he resurrects each time he dies. The caveat is that he risks losing his memories whenever this happens, which is exactly how the game begins.

A Meeting at the Smoldering Corpse Bar

“Here? This is the Smoldering Corpse, though the person smoldering ain’t dead yet.”

TNO’s only clues to his past are rather vague; all he knows is that he’s missing a journal and should seek out a man named Pharod.

Sigil is a wondrous city, but in some ways it’s not that much different from a typical fantasy hub. To get a few quick answers, the easiest solution is to visit the local tavern.

The gruesome Smoldering Corpse bar is filled with all sorts of interesting characters, one of whom is noted to be observing TNO. His name is Dak’kon, and he’s a withered old githzerai who wields a shimmering glaive.

Talking to Dak’kon reveals that his weapon, a karach, is shaped and sharpened by his mind. The karach represents a zerth, a follower of Zerthimon, but Dak’kon’s blade is somewhat degraded due to a spiritual crisis. The githzerai dwell in the ethereal world of Limbo, forging their surroundings from clear thought, so this is a fairly significant issue.

Unfortunately Dak’kon cannot answer TNO’s immediate questions, but when the conversation ends, he offers to accompany us on our journey.

Getting to Know Dak’kon

“This is his gallery. He says that he *knows* you as his canvas. He shows respect to your strength with his admiration.” Dak’kon is silent for a moment. “Then he insults you by giving you his pity.”

The initial conversation options with Dak’kon are limited, but talking to other githzerai in his presence reveals more about him. We pick up on the fact that Dak’kon’s sullen disposition is a result of what’s seen as a terrible disgrace by his people.

What’s more, Dak’kon is purposefully hiding things from us.

In the Weeping Stone Catacombs, TNO comes across a severed arm that once belonged to his previous incarnation. The arm can be taken to Fell’s parlour to ask the Dabus about the tattoos that adorn it. If Dak’kon is chosen to translate Fell’s rebus dialogue, TNO can detect that the seemingly honourable gith is actually lying.

When confronted, Dak’kon states that he will not say any more in the parlour. The issue can be pursued later on, at which point we discover that Dak’kon has actually traveled with one of TNO’s previous incarnations. This revelation leads to the rather unique Xachariah subquest that sheds more light on TNO’s own past.

Learning the Circle

“*Know* that I am not a teacher in this, but *know* that I can serve as a guide.”

When TNO asks Dak’kon about his magic — the ‘Art’ — the gith replies that he does not know how it manifests itself in humans. However, if TNO were able to use it, he could learn more of it from Dak’kon.

This is achieved by completing Mebbeth’s sidequests and becoming a mage. While a mage, TNO can study under Dak’kon, and also switch classes by talking to him.

“To learn, you must *know* the People. To *know* the People, you must *know* the Unbroken Circle of Zerthimon.”

The Unbroken Circle of Zerthimon is a device composed of a series of interlocking stone carvings. It’s a clockwork bible of sorts that Dak’kon carries with him wherever he goes.

Examining the Circle as a mage opens up a dialog box. Each level of the Circle tells a different tale of the githzerai race, its genesis, mass enslavement, and eventual rebellion. It reveals the rise of Zerthimon and the eons of suffering him and his people endured. The Circle teaches how the zerth came to learn and master themselves, and how enslavement became their greatest anathema.

“Endure. In enduring, grow strong.”

The full transcript of the Circle’s teachings can be found here, although it doesn’t contain Dak’kon’s and TNO’s commentaries.

Reading and learning the Circle comes across as a ritual; TNO must unlock each layer himself — as shown by Dak’kon — and talk to the gith after each session to discuss it. If TNO’s wisdom statistic is high enough, the proper lesson can be gleaned. This rewards the party with some experience, and a unique spell disk for TNO that magically slides out of the artifact without diminishing its weight or content.

This pattern goes on for six lessons until it’s revealed that Dak’kon himself does not *know* the full Circle.

Teaching the Circle

“You performed a great service for me. In so doing, you enslaved me.”

With the sixth layer, both TNO and Dak’kon receive a new spell. To unlock the seventh and eighth layers, TNO’s intelligence must be high enough to work the mechanism, and his wisdom high enough to understand the lessons themselves.

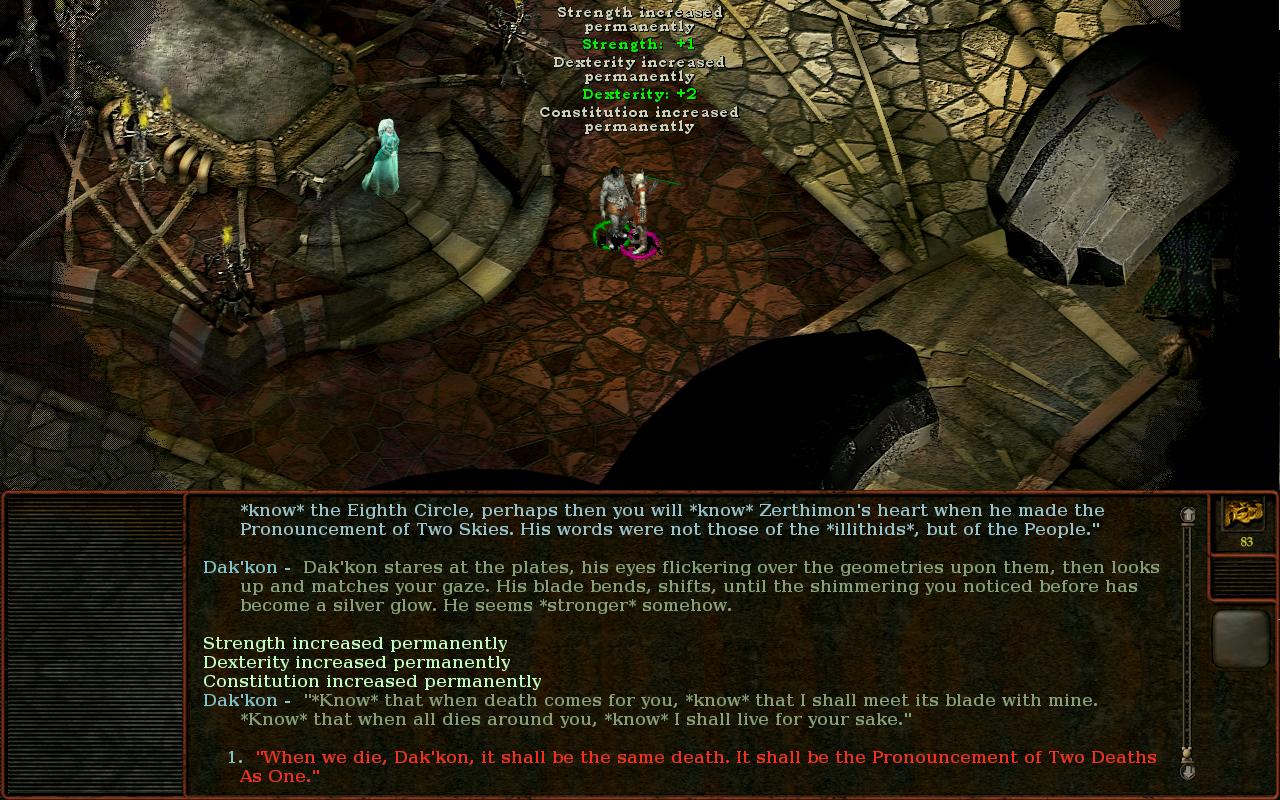

This is a nice transition of student-to-teacher, and ultimately rewards Dak’kon with some permanent stat increases. These in turn affect the karach blade, empowering it with each increment.

The lessons of the Circle also lead to the truth behind Dak’kon’s and TNO’s past.

The ruthless “practical” incarnation originally found Dak’kon close to death in the world of Limbo. He desired the karach blade, so he ensnared the gith in a devious trap. By constructing the Unbroken Circle of Zerthimon and speaking of its lessons, he showed Dak’kon a glimmer of hope to his spiritual ailment. In exchange, Dak’kon promised to follow TNO until his death, effectively becoming bound to the immortal for all time.

This enslavement constituted the greatest sacrilege for the zerth, yet it was the only salve for Dak’kon’s moribund soul. By completing the Circle, we finally brought him the resolution he so desperately craved.

Conclusion

“*Know* that there is now nothing left that I may surrender except my life.”

Although still bound to TNO, completing the Unbroken Circle of Zerthimon allowed us to strengthen Dak’kon’s body, mind and spirit.

The process also facilitated character development and character progression. It was meaty, and deep, and unfolded gradually as the game progressed. It sparked numerous discussion that are still ongoing to this day, and it’s held up as a prime example of what made Planescape: Torment such a compelling title.

And it was all for a completely optional character.

Loved the game, although it dragged on at times. The Unbroken Circle of Zerthimon, the showdown with Ravel, and the Sensorium definitely made it worth it.

“There cannot be two skies!”

This is exactly why Planescape Torment was such a kick ass game!

For all the talk of the conversations in Dragon Age, The Unbroken Circle of Zerthimon (and other parts of PT) were much deeper and more fulfilling.

Yeah, DA’s dialogues definitely felt more by-the-book. Maybe it’s the eclectic setting of Planescape, but its cast seemed much more varied and interesting.

I get the same vibe from DA II in particular.

While I enjoyed the game, it was very…symmetrical. Each character had the same number of quests, one per chapter, and they all unfold in similar fashion. There was also some unique banter that increased the binary friendship/rivalry statistics, and each companion had a few armour/gift upgrades, but they all followed the same format.

It’s as if a certain amount of time and resources was planned for each character. Of course this is quite natural from the production point of view, but it showed through in the gameplay. It’s simply too systematic to have each characters persona come through at the same intervals with the same amount of text and questing.

That’s definitely part of it. Planescape: Torment’s characters just felt more organic whereas Dragon Age’s all felt like they were all cut from the same cloth as far as the quantity of their dialogue/quests/etc.

I agree. What’s irritating is that so few gamers (relatively) know of innovative greats like Planetscape – or Pharaoh, or Heavy Rain, or even Uncharted for that matter. Its all marketing and hype.

Just as an interesting bit of trivia, while only a few lines in the game were actually voiced, Dak’kon’s dialogue was done by Mitch Pileggi—also known as Skinner on the X-Files.

Really? I never would’ve pegged Dak’kon’s voice for that of A.D. Walter Skinner!