All sorts of entertainment media use the concept of secrets to add intrigue and evoke a powerful emotional reaction. A strong effect of unveiling a secret can be the validation of the observer’s perceptiveness and reasoning; a wink wink, nudge nudge for being such a smart cookie.

However, most forms of media tend to be strictly passive. Aside from the occasional dabbling in interaction, the audience exerts no direct influence over the medium’s content.

Games — and videogames in particular — are inherently different. They are interactive and require players, not just observers.

There are plenty of lists online cataloguing the “best secrets in videogames,” but before we delve into this discussion, let’s actually define the term:

secret, n.

- Something kept hidden from others or known only to oneself or to a few.

- Designed to elude observation or detection.

Now let’s apply this denotation to design in videogames.

By definition, the secret needs to be explicitly known by someone, namely the person(s) implementing it in the game. It is also suggested that the implementation should be somewhat veiled and not immediately identifiable by the player. Since the implementation itself requires time and effort — possibly from various people responsible for design, production, programming, art, audio, QA, etc. — it should not be a wasted effort. In other words, the player should be able to discover the secret on account of all the work that went into creating it. Furthermore, to maximize the number of individuals who can access the secret, it can be assumed that it should be intrinsically tied to the default software and hardware and not rely on any arcane knowledge of the product.

Given the above, we can now define the “videogame secret”:

videogame secret, n.

- A hidden part of a videogame purposefully included by its creators with the intention of being discovered by the audience without any aid outside of the game itself.

This is not in any way official, but rather a clarification on my own definition of the concept. Using it to go forward, we can immediately strike down a bunch of entries in the above “best secrets in videogames” lists.

First, let’s eliminate anything that relies on outside interference. Mods, Game Genie/Pro-Action Replay/GameShark codes, special controllers and disk/cartridge swapping is out. As much attention as Hot-Coffee received, Rockstar did not want it exposed to the player. Well, unless you subscribe to the theory that it was always their intention for the content to get out, but that’s a whole other can of worms.

Second, glitches don’t count. Glitches are unintentional bugs that got past the QA process. Although certainly fun and interesting in some cases, as with Metroid’s secret worlds, they are the opposite of deliberately placed secrets.

Third, emergent gameplay is not a secret. Sure, combos are an integral part of Street Fighter II, but, as the story goes, they were not an intentionally designed mechanism. Fortuitous or not, emergent gameplay belongs more in the dynamics category than anything else.

Fourth, more often than not, cheat codes are simply debugging aids for the development team. Sure, the player can still access the ones left in, but most get disabled before the release of the title.

The ones that make it through tend to be a consequence of the developer’s/publisher’s quality assurance practices. If the QA department uses cheat codes to help them do their job, then at the end of the project there might be weariness when it comes to removing them as it might introduce all new bugs.

Now some cheat codes like the Konami Code have become quite famous, but how many of you would’ve known about them if it wasn’t for magazines, cheat books, internet sites and schoolyard gossip? It can be a bit of a gray area, but even intentional cheat codes are usually targeted at only the hardcore player. They tend to rely on communication and knowledge separate from the base product, therefore it could be said that they fall more into the fanservice category.

Oh, and password-restored game states and other rewards doled out directly by the game are not really cheat codes. At least not in my book.

With that out of the way, let’s talk about what I consider actual videogame secrets. There are plenty of famous ones such as Metal Gear Solid’s battle with Psycho Mantis, Diablo II’s cow level and the original “easter-egg” in Adventure, but I’d like to discuss three of my favourites (in no particular order).

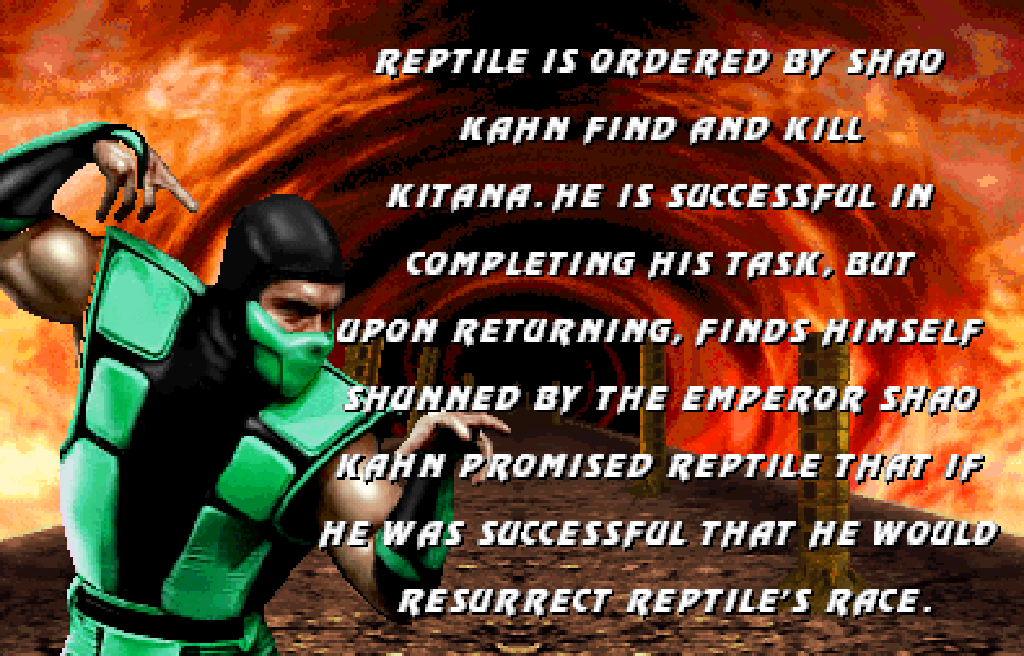

Reptile in the Original Mortal Kombat

So why was this secret so good? A couple of reasons:

- The game explicitly dropped clues for the player without disclosing the whole mystery. This encouraged deductive work and experimentation, and helped to generate even more excitement about the game (which it certainly wasn’t lacking with its digitized graphics and bloody fatalities).

- It teased the player with the character himself — a green version of two of its most popular cast members: Sub-Zero and Scropion — and the promise of encountering him somewhere in the game. The player didn’t know anything about Reptile’s abilities, where the encounter would take place, how it would play out, etc., letting his imagination fill in the blanks with tantalizing possibilities.

Reptile became a playable character in Mortal Kombat II with an all new moveset. - Getting to fight Reptile involved nothing more than using existing game mechanics, and it was not a prerequisite to completing the game or enjoying it on any other level.

- The actual Reptile fight took place at the bottom of The Pit, an area that was only briefly shown during another secret of sorts: the stage fatality. This is significant because it’sa location that the player only got a glance at, but was never able to explore. Setting the fight in this area is an excellent example of wish-fulfillment due to the common desire to experience such teased locales first-hand.

- Defeating Reptile earned the player not only bragging rights, but also a huge points bonus that would skyrocket him to the top of the high-scores charts.

Too bad he wasn’t playable, huh? (Incidentally, the honour of being the first secret playable character in a “vs” fighting games goes to Akuma.)

Reptile also worked well because everything surrounding him didn’t really require any new resources. All his art consisted of a simple palette swap. Likewise, his moveset was just a combination of Sub-Zero’s and Scropion’s, with a bit of speed thrown in. Even his custom stage was already there, just never previously used as the background for an actual fight.

The Inverted Castle in Castlevania: SotN

SotN is filled with all sorts of secrets: random item drops, hidden rooms and passages, artifacts that grant special abilities, etc., but the inverted castle has to be the most significant of them all. The idea of flipping a tilemap upside-down isn’t new, but this secret had a lot more going for it:

- To gain access to the inverted castle, Alucard had to go through a series of steps culminating in a battle against Richard Belmont, the protagonist of the previous games. Even without knowing the series’ history, though, this should seem suspicious. The game starts off with the player controlling Richard Belmont and squaring off against Dracula, a brief reenactment of the previous entry in the series. If the game’s finale turns out to be a fight against Richard, it’s easy to come to the conclusion that something was overlooked. After all, Alucard’s mission was to destroy the ancient vampire, not his friend and ally.

Richard Belmont facing off against Dracula — a recreation of the previous game’s finale. - Up until the fight between Alucard and Richard, it is impossible to fill out all of Alucard’s various spell/morph form/familiar/etc. slots. This might seem like a fairly insignificant fact, but it’s a clear indicator that the player hasn’t done everything there is to do in the game. Not even close.

- SotN encourages exploration of every nook and cranny, and this should easily result in the player finding two distinct rings. The rings’ descriptions read “Wear…Clock…” and “…in…Tower” respectively. Unlike many other items in the game, acquiring these rings is also accompanied by story events in which Maria, one of game’s pivotal characters, informs Alucard’s of Richard’s mysterious disappearance.

- The Clock Tower is located right in the middle of the castle, and is a unique area not duplicated anywhere else in the game. Adding to its significance is the fact that it is the only place in SotN where background elements automatically move just a single time. What I mean by this is that whenever Alucard enters the Clock Tower, slaps of concrete magically slide in to close off possible paths of exploration. This happens every time the area is visited, and although it relates to another secret in the game, it helps to make the room feel that much more important.

Alucard racing toward his father’s castle. - Bringing and equipping both rings (most players seem to miss that second part) to the Clock Tower opens up a new passage. In this secret area, Maria informs the player that Richard is being controlled by Shaft, another old villain in the series. In order to defeat Shaft and save Richard, she gives the player a pair of Holy Glasses that, when equipped, allow Alucard to see and attack a green orb floating above his friend’s head.

- Destroying Shaft’s mind-controlling orb unlocks the passageway to the inverted castle where lots of new enemies, bosses, items and abilities await Alucard, almost doubling the content of the game.

As far as rewards for discovering secrets go, nothing has topped SotN’s enormous wealth of content in its wholly optional inverted castle.

The First Warp Zone in Super Mario Bros.

Quite possibly the most recognizable videogame secret is the hidden warp zone at the end of level 1-2 in SMB. Now Super Mario Bros. was a somewhat surreal game, but much of that was due to the kind of reactions it tried to evoke from the player. It’s a topic that deserves its own article, so for now I’ll just cover how it made the warp zone so great:

- In various parts of the first stage, the player can reach — and “break through” — the ceiling of the level. This teaches him that, unlike the pits, there’s no penalty for going outside the top part of the map.

While powered up, it’s impossible to make this jump and snag the coins without busting through the screen’s ceiling. - In level 1-2, there are numerous locations where the player (provided he’s in the powered-up Mario state, which is always in his best interest) can smash through the brick ceiling. This ensures that the player thinks of it as a barrier he can breach. Furthermore, if the player experiments a bit, he can actually get over and on top of it where he can freely maneuver.

- The level ends with a pit area filled with an endless stream of upwards-moving platforms. The platforms overlook the level’s exit and a continuation of the brick ceiling. Based on the player’s experience, he knows he can make the jump from the platform to the top of the ceiling provided there’s no invisible wall blocking him. Furthermore, if he misses the jump, it’s apparent that he’ll land in a safe place as the ceiling doesn’t extend as far toward the platforms as the ground area.

The fabled warp zone itself. - Upon making the jump and — while overlapping the HUD — running past the exit pipe, the player finds himself in the warp zone. This area allows him to enter any one of the three pipes leading to their corresponding worlds, effectively allowing him to skip ahead in the game.

Not only was this secret memorable as it allowed the player to finally breach the end-level area (from what I recall, jumping over the flag-pole was nigh-impossible as it was an unintended bug), but it also rewarded him with the ability to fast-forward through the game. This was a feature all the more significant as SMB did not contain a password or save system allowing similar functionality.

What’s really interesting here is that all of these secrets have a few things in common:

- They’re not explicitly revealed to the player, but they’re not overly obfuscated either. All the hints required to discover the secrets are also presented to the player in the games themselves.

- The hints — and the promise of potential secrets — encourage the player to experiment. Through deduction and some general “messing around,” the player can discover the secrets by himself using gameplay mechanics that are already familiar to him.

- The secrets are wholly optional. One might make a case that SotN’s “true” ending cannot be reached without exploring the inverted castle, but an ending still exists regardless of whether Richard Belmont is saved or defeated.

- The secrets are rare, and their sparing use only adds to their significance.

- All the secrets present a notable reward for their discovery, helping to give the player a great sense of accomplishment once they are unveiled.

Now these points aren’t golden rules — there are, for example, good secrets in videogames that are repeated over and over again — but they all help to make the above entries stand out.

Secrets themselves are not required to create great games either; a wholly static, linear and transparent experience can still be quite enjoyable.

Secrets can, however, add that extra bit of magic.

By allowing the player to explore the game (no matter how much actual exploration can take place), we imbue it with a sense of wonder and adventure. This helps to highlight the interactive aspect of videogames. It gives the player the choice to see what’s around the corner — we just have to make it something good.

Now I really want to see that article on Mario.

Heh, thanks — now I have that obligation to actually sit down and write it.

Most interesting article. Thank you.

Cool list. Thanks. I would also include the whistles in SMB3 too, but thats kinda clique, heh.