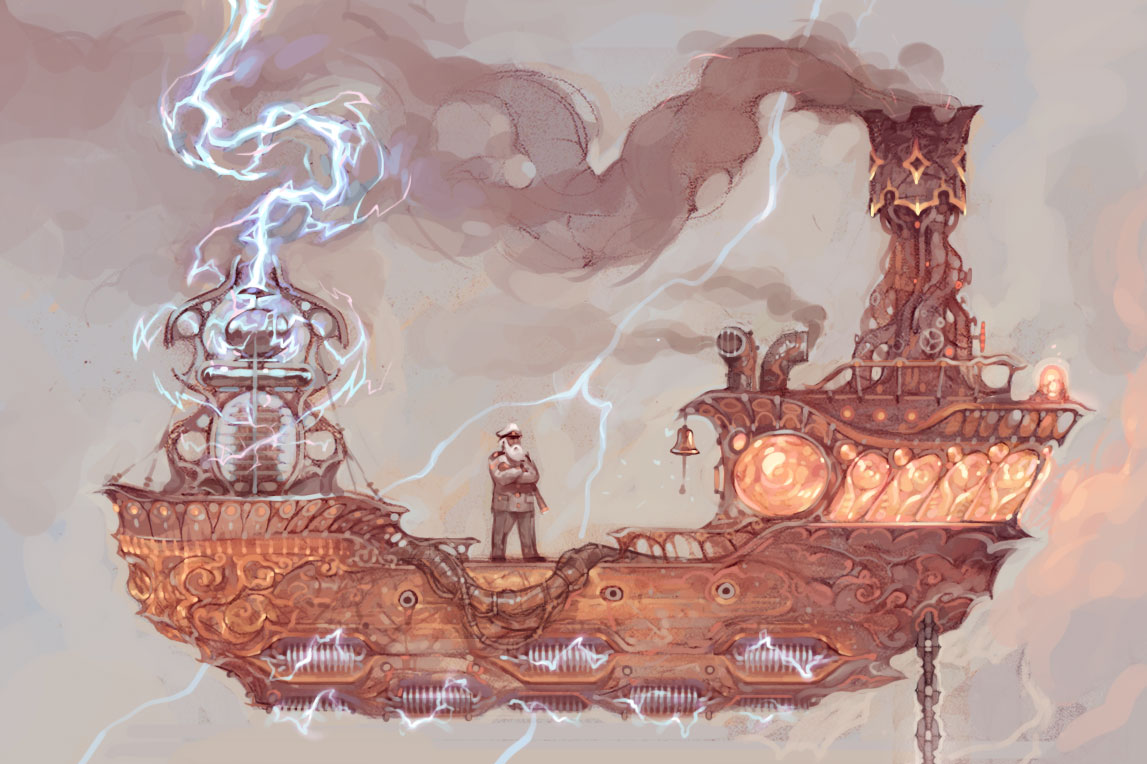

Trudy’s Mechanicals is a turn-based strategy game that pits a host of combat veterans, bespectacled scholars, and industrial labourers against the corrupt gentry of a Steampunk airship.

The success of XCOM: Enemy Unknown proved there was a substantial audience for turn-based strategy games on PC. Being fans of the genre, everyone at Incubator Games was excited about following suit with our own tactics title. I kicked off this process by playing through some of the more successful console and PC tactics games and analyzing their design.

For each game I noted its strengths and weaknesses and catalogued critic-reviews along with rough sales numbers from VGChartz and SteamSpy. A few takeaways from this exercise:

- Console titles had a strong focus on unique characters while PC games prioritized character creation and customization.

- PC titles tended to revolve around player uncertainty and dice-rolls; no attack was a guaranteed hit and fog-of-war hid extra dangers.

- On both platforms there was no way of previewing whether an ability could be attempted after movement finished, and there was rarely an option to undo a turn.

- Console titles tended to mimic each other’s interfaces and often included unnecessary confirmation prompts and interlude screens. Controls also rarely accommodated the most common use case, e.g., it often took as many actions to use an antidote (rare) as it did to launch the default attack (common).

- Maps were generally more sprawling on PC and contained basic environmental interactions such as opening doors and destroying obstacles. Both platforms still used the environment passively to grant attack/defense/movement bonuses and penalties.

Based on these findings, we decided to create a game that merged the more asymmetric gameplay and narrative-focused elements of console SRPG’s with the streamlined interface and dynamism of the XCOM reboot. This would not only bring some relatively new elements to PC tactics games, but also allow our company to expand its 3D capabilities and genre-expertise.

To make sure we weren’t in over our heads, we put together a tech-prototype to help capture the challenges of the project.

The endeavour helped greatly in paring down the needs of the game while defining its overall scope. These lessons — and the proof-of-concept itself — were also vital in successfully pitching for OMDC’s IMF grant to aid in funding development.

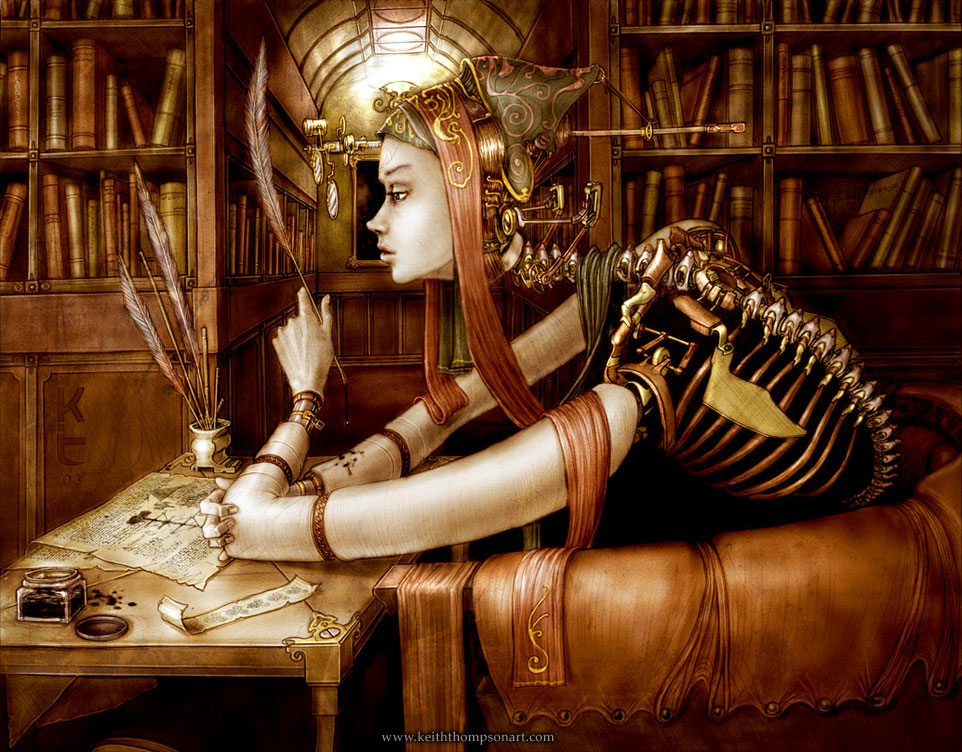

Right from the get-go, we set the game aboard an airship to organically limit its scope. An underutilized (at the time) Steampunk aesthetic seemed like a natural fit for this motif, so I compiled a long list of references for our artists.

Something that I prioritized early on was the setting itself informing story and gameplay. Steam engines, bulky goggles, and a plethora of clockwork watches were an iconic aesthetic of Steampunk, but there had to be a reason for them to exist. Consequently, I attempted to answer a lot of questions about the setting that would logically follow our plans for the game:

Why was everyone stuck on an airship?

Fallout from the pollution caused by the vast amounts of coal-burning steam-engines.

What was the reason for people to “mechanize” themselves?

Mainly the lack of oxygen so high up in the air, and the necessity to stay productive while avoiding Hypoxia.

How long was the airship floating and where was it heading?

No one seemed to know, which was partly the reason for the people’s discontent and eventual rebellion.

Class warfare is a common trope of tactics games, so I also wanted to incorporate greater mysteries and conflicts into the game. Taking inspiration from Ted Chiang’s short story _Seventy-Two Letters_, I conceptualized a setting where various obsolete scientific theories were factual. Homunculi doctors treated humor-imbalances, immense punchcard-AI’s probed the secrets of Vitalism, and those beyond the Firmament beamed down cryptic messages.

Ultimately not all of these concepts made it in-game, but they helped to create a more consistent and cohesive game world.

Finally, to set Trudy’s Mechanicals apart from other Steampunk media that relied heavily on Victorian tropes, I pushed for a more Slavic and Greek interpretation of the genre. In particular, the language I used in the game was designed to convey a sense of history while evoking a Balkan flavour. Renatus and Daria became common character names, conversations were peppered with old slang like lushery (a bar) and nibbed (arrested), and foreign proverbs were common in cutscenes:

Gray hair is a sign of age, not wisdom.

Eat and drink with your relatives; do business with strangers.

Many have loved treason, none the traitor.

Trudy’s Mechanicals starts with the player discovering blueprints for a printing press, and ends with the seizure of the airship itself. This is done over the course of roughly 35 main storyline missions, with small acts of sedition slowly leading to a full-scale rebellion.

Story missions were played in a linear order, but between each one the player could engage in lots of optional content. The campaign was balanced to be feasible via a straight playthrough, but was substantially easier if optional upgrades and resources were pursued.

Unlike the power-fantasy of Disgaea or the horror elements of XCOM, Trudy’s Mechanicals was a war of attrition, albeit with a constant sense of progression. Every successfully completed event granted a permanent upgrade: a new unit or unit upgrade, a gameplay-altering gadget, a boost in popularity with neutral units, intel for future missions, or new optional events.

All of the mandatory and optional events were initiated from the main hub of the game: the ship view. This represented the game’s largest loop where decisions were made on which units to hire, what upgrades to unlock, and whose leads to follow.

Each node on the ship view represented one of the following events:

Story Mission – the next battle to play in order to progress the plot. Always available with a focus on using the main characters.

Newspaper – a special non-interactive update via a narrated editorial. Appeared throughout the game every time a handful of story missions was completed.

Side Mission – an optional battle that is entirely funded by the player. Only a single main character and their hired help can engage in these encounters.

Cutscene – an interactive segment that provides extra narrative and can award additional resources.

Arena Battle – a free-to-enter combat scenario with its own custom rules and rewards.

Both story and side missions were heavily scripted to provide narrative context and gameplay variety. Mission objectives changed from event to event and included goals such as sabotaging enemy defenses, escaping an ambush, defeating a boss unit with its own unique gameplay modifiers, and protecting a certain location from waves of assailants.

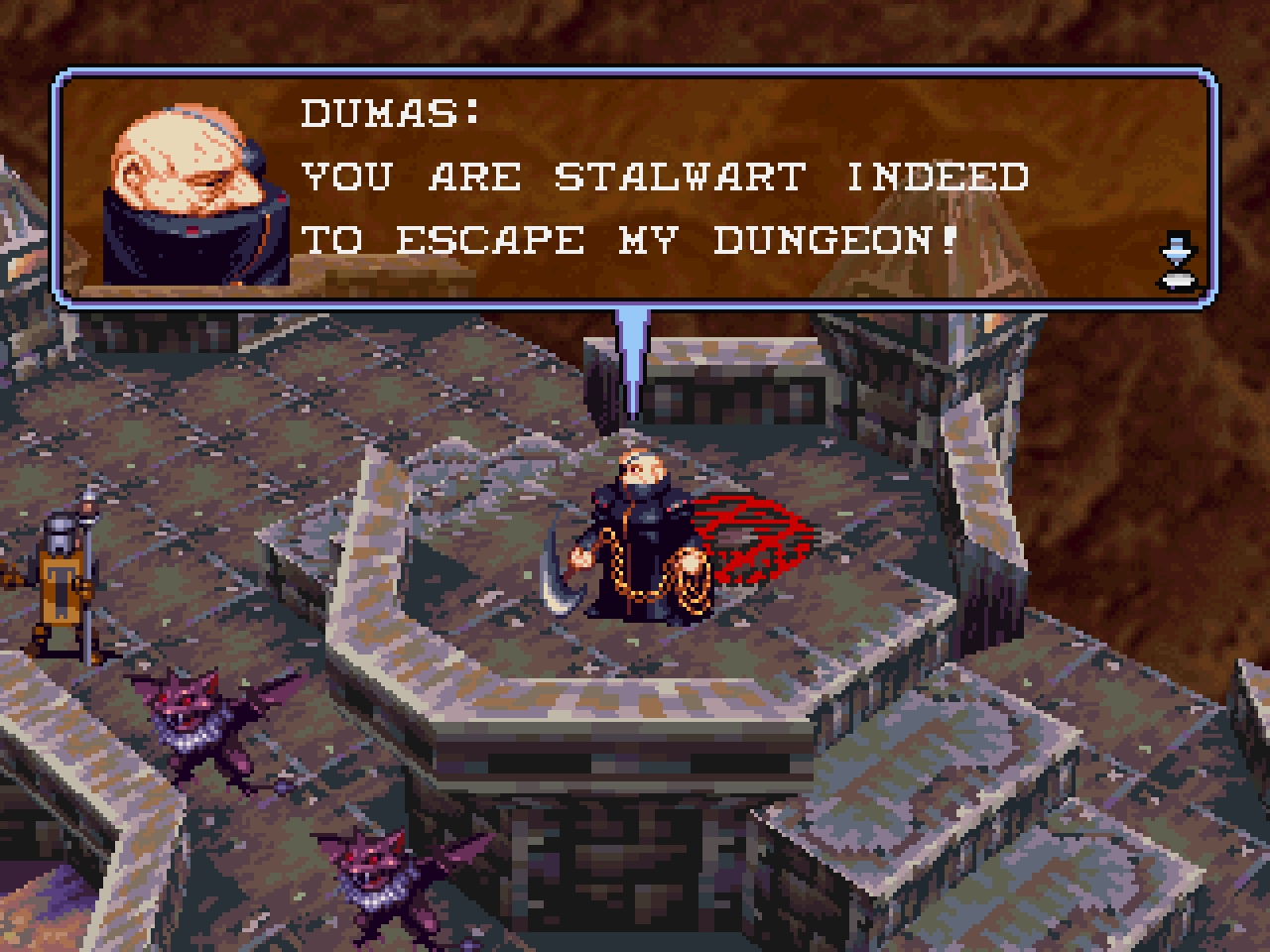

Interactions in cutscenes were largely done through selecting dialog options and interacting with environmental objects. Due to the lack of lipsynching, the use of lower-poly models and lower-res textures, and the animation requirements for complex cinematics, I looked to older titles for inspiration. These typically relied on a robust camera system for panning, rotating, zooming, cutting, and following smooth curves to create a sense of dynamism, and I strove to emulate their presentation in our scripted segments.

Keeping our budget constraints in mind, I decided to save voice overs for in-game barks/exclamations and the most important scenes in the game. This included the newspaper segments that punctuated important moments in the story. Below are a couple of samples that I wrote and recruited voice actors to record:

Finally, arena battles featured their own progression and rulesets, but no narrative elements. Each time the player visited one of the three arenas, its mission was randomized to provide different goals, opponents, and combat restrictions.

An audience was always present at arena battles, rewarding aggressors with health drops and punishing cowards by lobbing explosives at them. This was partly done to facilitate multiplayer — which took place exclusively in arenas — and partly to limit unit-composition exploits, i.e., if fast units were continuously used to run away, the crowd would step in to even the odds.

Another dial for balancing multiplayer was giving each player a set amount of money to spend on their units, which also opened the door for including high-cost troops not recruitable in the main storyline. The combination of these elements allowed us to focus on making the units as varied as possible without worrying too much about balancing specific rosters.

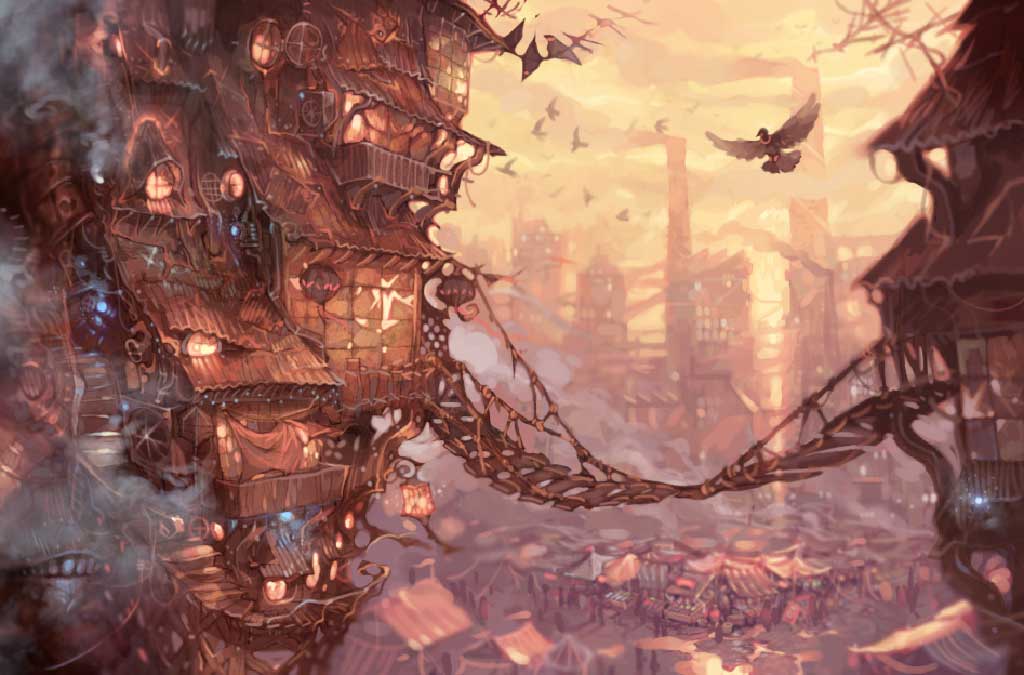

Despite the setting being a singular airship, it was important to create aesthetic variety within the game. To that end, I planned numerous distinct biomes that emerged aboard the airship over time.

The original prison cells became home to the poorest Mechanicals, the inner storehouses suffered a punchcard virus and went amok, Trudy’s surface was expanded with various factories and warrens, and vast hanging gardens were built at the stern to feed the masses. Eventually Trudy encountered other skybound entities, attaching a series of mysterious floating islands and the shell of a clockwork AI to its hull.

Once the biomes were established, I created lists of aesthetic and gameplay props to create a distinct feel for each area, e.g., the Underworld was littered with toxic Sewer Slug eggs, the Aerie was protected by Gatling turrets and consoles that summoned city guards, the Labyrinths’ floor and wall panels randomly extended to crush intruders, etc.

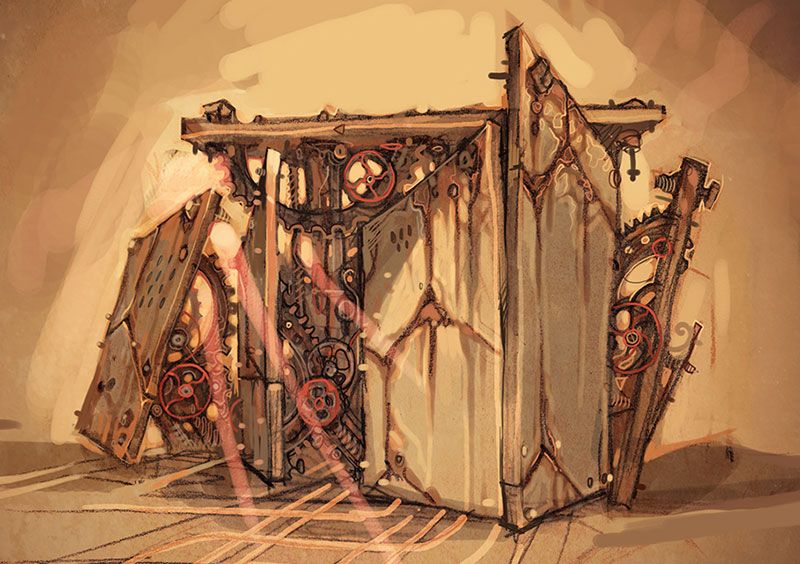

One of the top priorities for the project was to create a level editor for quick testing and prototyping. Due to the need to easily gauge distances in an isometric-style view, I heavily referenced Valve’s Puzzle Creator for the task.

The ability to quickly create a voxel-grid was crucial to greyboxing all of the game’s levels and experimenting with numerous gameplay elements. Movement and jump ranges, pathfinding, slope and small-bump traversal, collisions, falling, pushback, and many other mechanics were solidified early on thanks to this approach.

A few of my initial test maps made it evident that tight alleys obscured too much of the map, while flat and open spaces didn’t provide enough cover or movement variety. Prop density, spawn points, and overall scale were also solidified in the initial tests, giving me more time to experiment with the medium sized game-loop of missions: responding to the flow of battles and maneuvering the entire team to achieve specific objectives.

To keep scope in check while still providing some variety, the finished levels were further tweaked in the scene editor. Each scene was customized to add/remove props and cordon off the playing field, creating brand new challenges in existing maps or showing an area from a new point-of-view. Scenes were further customized with additional lighting, particle effects, vehicle movement, spawn locations, and combat scripting.

The final polishing phase added stencil shaders to show obscured fighters, mouse-over highlights for destructible props, and support for removing entire walls based on scene-rotation to provide a clearer view of the battlefield.

In many ways, the cast of Trudy’s Mechanicals is what set it apart from other tactics games.

Creating the fighters was something of a holistic process. I drafted ideas for general Steampunk battlers, labourers that could occupy the airship, miscellaneous abilities that would be interesting to use in combat, and passive properties that would influence optimal play. All these lists were eventually merged, creating the final roster.

Taking a cue from fighting games and MOBA’s, I designed each battler to have multiple unique abilities. There were no simple attacks as even common melee strikes were all varied; they possessed different ranges and could combo into additional hits, inflict status effects, target multiple opponents, land criticals, exploit elemental weaknesses, or move the target or attacker. The goal was to have no redundancy by making each skill clearly distinct.

Unit synergy — boosting an ally’s capabilities while compensating for individual weaknesses — was also an important consideration. For example, Sewer Slugs left behind a toxic trail as they moved — this damaged most units, but Waspmongers could travel through it without a penalty while other Sewer Slugs actually got a boost to movement while in the sludge.

Along the way numerous units and well over a hundred abilities were discarded. However, the brainstorming work helped to scope out the incredibly complex gameplay needs and provided alternatives for problematic units and abilities.

Taking in the battlefield and optimally using the current unit served as Trudy’s smallest game-loop. Since certain situations could arise where a unit was too far to interact with objects or enemies, I made sure to include plenty of “power-up” abilities that empowered the unit itself such as the Sentinel consuming all his ammo to give his melee attacks increased damage and a chance to stun.

It didn’t make sense to give every unit a powerup ability, so I also enhanced each basic “defend” command with an additional boost: Bauk spun his shield to deflect incoming projectiles, the Mechanic healed himself without consuming ammo, Renatus flared up his jets to temporarily extend his movement range, etc.

As abilities required a large amount of customization, their data was stored in flexible JSON files. However, the more standardized requirements of unit statistics resided in a CSV file alongside plot progression, mission requirements, unlock paths, etc.

Movement ranges, turn-priorities, and all other common statistics started from the same baseline for each unit, but were offset to reflect certain roles, e.g., the tanky Bauk was slow but had a high defense, the agile Koschei could leap across large gaps and got his turn early on in the round, the fragile Beholder had low health but was resistant to bio-damage, etc.

During development, builds of the game were left running overnight with groups of AI units battling it out. Logs from these fights were used to discover bugs and problematic edge-cases, but the actual balancing was done strictly via playtesting due to unit asymmetry.

The opposition AI didn’t function as a cohesive whole as the goal was to accentuate unit personality. Outsmarting the enemy is a satisfying staple of tactics games, so I prioritized different behaviours based on unit archetypes — the greedy Ravagers sought out chests and looted bodies, the distinguished Butler Bots prioritized retaliating against units that damaged the environment, the crazed Automatons attacked a random enemy each turn, etc.

These behavious were set up via a list of paired context/action checks, e.g., if a friendly unit is in critical health, heal them. Additional weights were placed on checks to occasionally bypass them, preventing unit behaviour from being wholly predictable.

When it came to translating the aesthetic of the concept art into the game, I stressed following Dota2’s Asset Creation Guidlines. The perspective of Trudy’s Mechanicals was similar to typical MOBA games, so many of the same lessons applied: unique silhouettes, distinct colour palettes, and top-to-bottom lighting.

Another element of MOBA’s I partially transplanted into Trudy’s Mechanicals was the idea of “skins.” In other games skins are typically aesthetic-only variations on a single unit, but in our game I used them to denote unit-upgrades.

To limit balancing scope and facilitate multiplayer, Trudy’s Mechanicals had no unit level-ups or customizable equipment. This made meta-upgrades incredibly important to gameplay progression, second only to unlocking new combatants themselves. Considering these upgrades awarded stat boosts and new abilities, the aesthetic variation was an additional reward that also helped to differentiate units at glance.

Finally, to provide ample references for particle and shader effects, I recorded various games in FRAPS and NVidia’s ShadowPlay, and scoured YouTube for playlists on Diablo III, League of Legends, and other games with a similar perspective.

Throughout development, I made sure to spend an hour or two each day gathering promotional materials and researching marketing opportunities.

I started off by posting samples of our work on development-friendly forums like TIGSource, IndieDB, GameDev.net, and IndieGamer. I then created a presskit for the game, sent out press releases, and performed a marketing audit.

The marketing audit led me to discover various wikis, fan sites, YouTube channels, enthusiast blogs, conventions, Kickstarter campaigns, curator lists, subreddits, Facebook groups, and gaming sites where tactics games were covered. These were all collated into an Excel file, and I bookmarked additional advertising campaigns and outreach initiatives that could prove relevant for our project.

As we began to approach outlets for coverage and Trudy’s Mechanicals started to get more attention, I made sure to answer any requests for info whether via e-mail or in person.

I also keyed in on one element of Trudy’s Mechanicals that other tactics games didn’t possess: the Steampunk setting. I catalogued Steampunk fan sites, zines, forums, and groups, noting their user-count and reaching out to their administrators. I made sure to follow them on social media and engage with them personally, not just in relation to our game, in or order to form the roots of a partnership.

Once we hired additional help for PR, I informed our social media coordinator of all existing leads and initiatives. We then set up a series of Google Alerts so we could directly engage with anyone interested in our game while continuing to participate in indie-centric promotions such as #screenshotsaturday.

In our weekly meetings, we monitored the performance of our social media platforms, discussed the content necessary to continue growing them, worked to improve our SEO by leaving a footprint on various wikis and indexing sites, and brainstormed ideas to further engage potential fans. One of these was to use the in-game newspapers to create additional “issues,” taking advantage of our worldbuilding docs and concept art to foreshadow mysteries and reveal stories not present in the campaign.

I tabulated all these endeavours and used the data as part of a pitch to publishers. This helped us showcase that we already had an audience and were actively participating in promoting our title.